In my last post, I mentioned that the FAA looks at many factors during obstruction evaluation studies. In fact, if you go down the rabbit hole to try to figure out everything that goes into one of these studies, it can get very complicated, very quickly.

Fortunately, you don’t need to go down that rabbit hole, because I’ve gone for you! And, I’ve reemerged with a summary of the key factors that the FAA considers when evaluating proposed wind projects.

In this post, I’ll share what makes a wind turbine a “hazard” in the eyes of the FAA and provide actionable insights for wind developers.

I hope you’ll find this entire post useful, but if you want to skip ahead to the takeaways, I’d recommend jumping here.

What is an “obstruction”, anyway?

Let’s start by defining what the “obstruction” in “obstruction evaluation” means. According to 14 CFR Section 77.17, a feature will be considered an “obstruction to air navigation” by the FAA if it exceeds one or more of the heights defined in its “obstruction standards”. For wind turbines, there are five obstruction standards that apply, summarized below1:

- Taller than 499 feet

- Near an airport with a runway ≥ 3,200 feet long and taller than 200 feet above the ground or the airport, with this height limit rising to 499 feet farther away

- Taller than the required clearance needed for takeoffs, landings, and other procedures near airports

- Taller than the required clearance needed for enroute airways (i.e., routes between airports)

- Taller than any imaginary surfaces2,3

Based on these standards, there’s a good chance your commercial wind turbine will be identified as an obstruction, since most modern utility-scale turbines are taller than 499 feet. But, that’s not the end of the world. Being identified as an obstruction is not a problem; being determined to be a hazard is. So, let’s move on to our next topic.

What are the criteria used for a hazard determination?

To find out what makes a wind turbine a hazard in the eyes of the FAA, we need to turn to FAA Order JO 7400.2. This document provides guidance for FAA personnel to administer the “airspace program”, including obstruction evaluation studies. Part 2, Section 6.3 provides a lot of valuable information, including two key points:

1. An obstruction is determined to be a hazard ONLY if it causes “substantial adverse effect” to the navigable airspace.

2. The FAA evaluates “substantial adverse effect” by looking at whether the proposed obstruction would affect “a significant volume of aeronautical operations”.

This means that to receive a hazard determination, a proposed turbine must not only exceed an obstruction standard, but do so where there is existing flight traffic.4 Avoid these two criteria and you should increase the likelihood receiving a No Hazard Determination from the FAA.

Avoiding Obstruction Standards and Air Traffic

So, how do you avoid obstruction standards and “significant” aviation traffic?

To answer this question, let’s circle back to the five obstruction standards used by the FAA. The first one – a height taller than 499 feet – stands out for two reasons. First, like I mentioned before, all modern, utility-scale wind turbines will likely trigger this standard, so there is no avoiding it. And second, unlike the other four standards, it is not dependent on any aeronautical features, so we shouldn’t expect it to have any correlation with air traffic. In short, avoiding Obstruction Standard #1 is not where you should focus your effort.

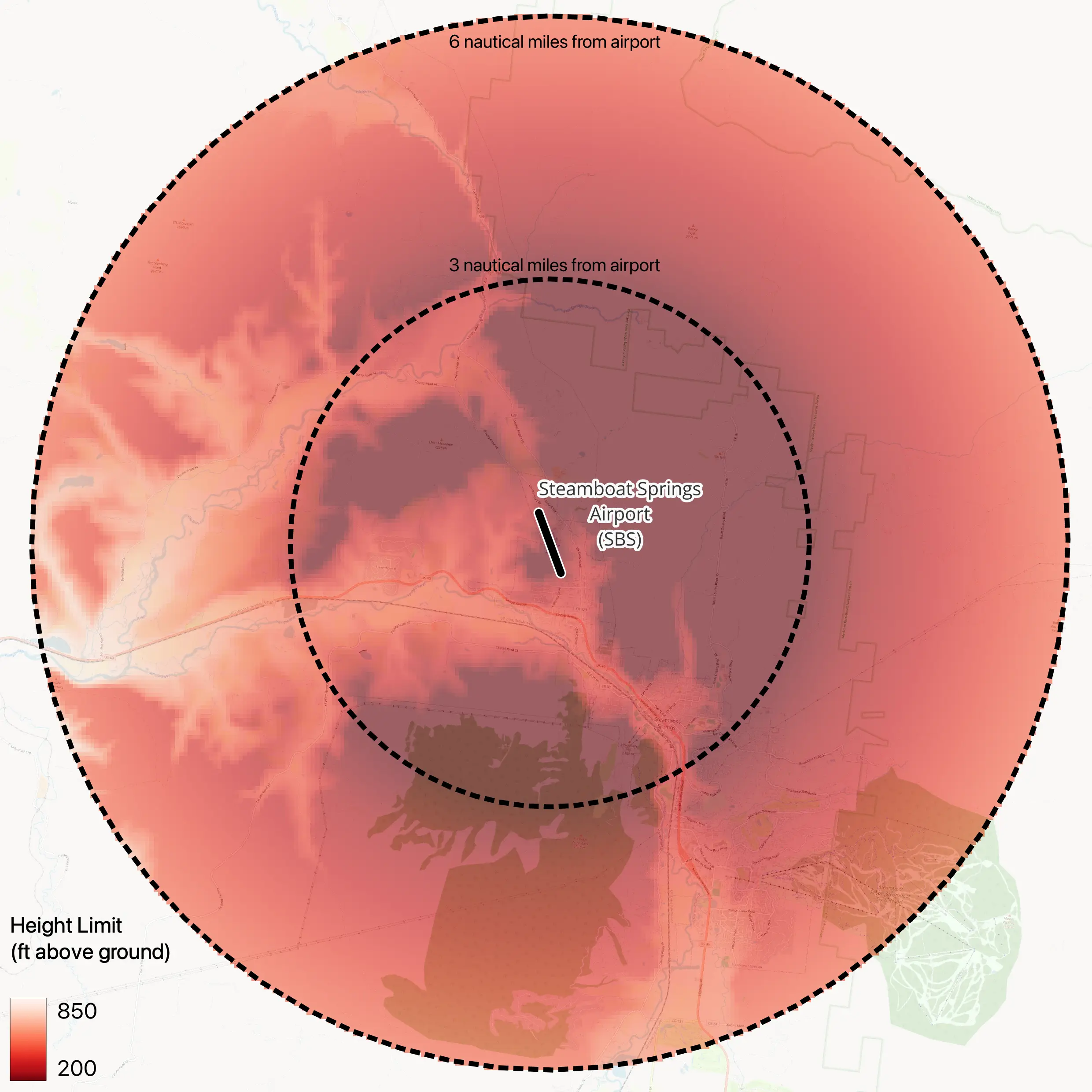

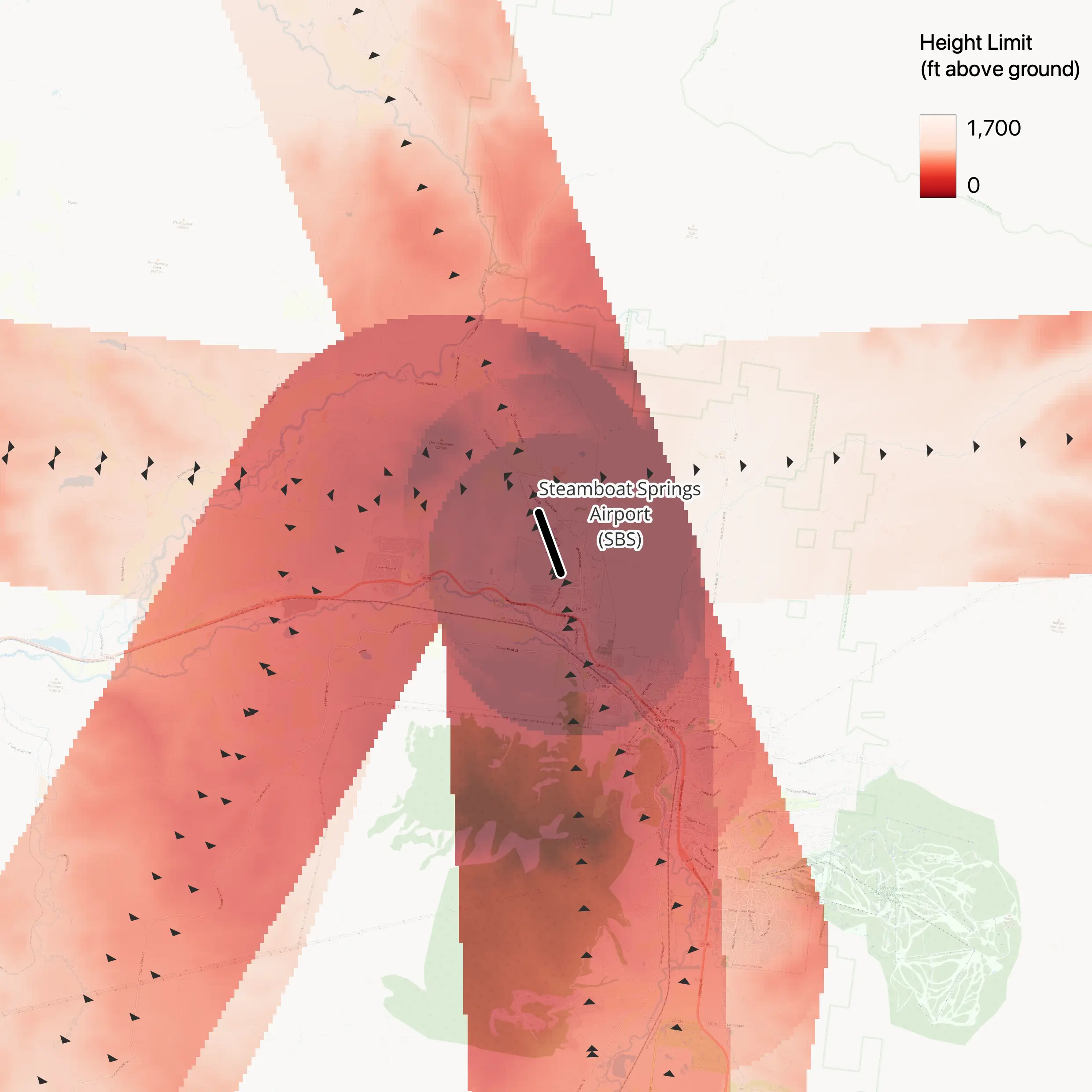

On the other hand, features related to the remaining four obstruction standards can be mapped and many of them are likely to correlate to areas that experience significant air traffic. As a result, there are opportunities to avoid them, their associated obstruction standards, and their presumed air traffic.5 See the table below for a list of aeronautical features that correspond to each obstruction standard. When siting your project, avoiding these features is where you should focus your effort .

| Obstruction Standard | Aeronautical Features |

|---|---|

| 2 | – Imaginary surfaces for civil airports (FAR 77.17(a)(2)) |

| 3 | – Published Instrument Approach Procedures for Civil Airports* – Published Instrument Departure Procedures for Civil Airports* – Minimum Vectoring Altitude (MVA) Sectors and Obstacle Clearance Surfaces |

| 4 | – Low Altitude Enroute Airways and Obstacle Clearance Surfaces* – Minimum Instrument Flight Rules (MIA) Sectors and Obstacle Clearance Surfaces |

| 5 | – Imaginary surfaces for civil airports (FAR 77.19)* |

Features with an asterisk (*) are likely to correlate with areas that experience air traffic.

Takeaways

So, if you’re a wind developer, what should you do with all of this information?

First, if you want to lower your chances of having to modify or cancel your project, try to site it away from areas where it will trigger any of obstruction standards 2 through 5. You can use our nationwide GIS datasets to do this, or work with a specialized consultant to help you map and understand the features for individual wind projects. Avoiding these areas won’t totally eliminate your chances of a determination of hazard or presumed hazard6, but it should substantially lower your odds.

On the other hand, if you have a site that is ideal for other reasons, but it exceeds obstruction standards, don’t abandon hope. It’s possible that your location doesn’t have significant air traffic and the FAA will make a Determination of No Hazard. However, you should be prepared to adjust your plans, if needed.

In my next post, I’ll show what it looks like to put this advice into practice. While I’m busy working on it, please check out our prior post about imaginary surfaces and contact us here or on LinkedIn if you’re interested in getting ahold of our datasets.

Notes

- For the complete, legal definitions of the obstructions standards, refer to 14 CFR 77.17. ↩︎

- See our previous blog post for a primer on imaginary surfaces. ↩︎

- Imaginary surfaces exist for civil airports, military airports, and heliports. Root Geospatial currently only offers GIS data for civil airport imaginary surfaces. ↩︎

- It is important to note that there are two other categories of factors that the FAA considers in evaluating the potential for hazard: (1) the potential for electromagnetic interference to the operation of an air navigation facility or signal used by aircraft; and (2) airspace and aviation routes used by the US military. Assessing these factors is much more complex than doing so for obstruction standards and air traffic. Typically, it requires specialized, sometimes restricted, information, and can only be performed by the FAA and/or Department of Defense, which is why I’ve left them as a footnote. They are, nonetheless, important considerations that could also result in a Determination of Hazard for wind projects. ↩︎

- You may be wondering if historical air traffic volumes can also be mapped. The answer is: theoretically yes, but there’s currently no easy way to get them. The FAA is able to assess historical air traffic volume as part of obstruction evaluation studies using archives that they maintain of airport surveillance radar data. In theory, you could place a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to receive these archives. There are also multiple companies and organizations that track flight paths in real time and maintain historical flight tracks, although they aren’t geared for this use case. Instead, they are focused on providing real-time situational awareness for all current flights and access to small subsets of historical tracks for specific time periods or specific aircraft. If you did manage to acquire a historical archive via either FOIA or a commercial source, my guess is that you’d find yourself in possession of an immense volume of data in unfamiliar file formats, leaving a lot of work to be done before you can import the data to your GIS software. ↩︎

- See footnote #3 for a discussion of other factors that are harder to preemptively avoid. ↩︎